Cultural identity

Māori language speakers

Definition

RelevanceTop

Māori language is a central component of Māori culture, and an important aspect of participation and identity. It also forms part of the broader cultural identity and heritage of New Zealand. In 1987, the Māori language was recognised as an official New Zealand language.

Current level and trendsTop

In the 2013 Census, 21.3 percent of all Māori reported that they could hold a conversation in Māori about everyday things. This was a decrease from 23.7 percent in 2006 and 25.2 percent in 2001. Of the 148,400 people (or 3.7 percent of the total New Zealand population) who could hold a conversation in Māori in 2013, 84.5 percent identified as Māori.

In the 1996 Census, one quarter of Māori said they could hold a conversation in Māori, and it remained at that level in 2001. Although there were around 1,100 more Māori who could hold a conversation about everyday things in Māori in 2006 than in the previous Census, the Māori population had grown by a greater number and so the proportion of Māori who could speak conversational Māori declined, from 25.2 percent to 23.7 percent. However, at the 2013 Census, the number of Māori who said they could hold a conversation in Māori had declined by 6,200 from 2006, further lowering the proportion of Māori who could speak conversational Māori to 21.3 percent.

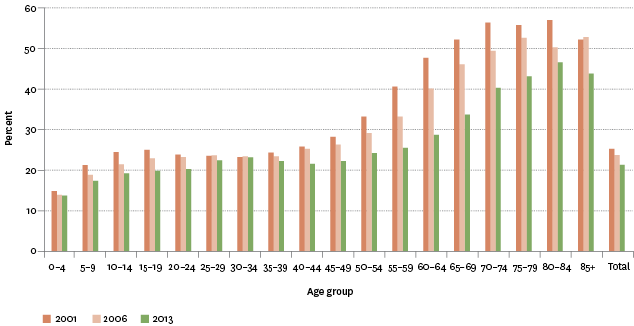

Figure CI2.1 – Proportion of Māori speakers in the Māori population, by age group,

2001–2013

Source: Statistics New Zealand, Census of Population and Dwellings

Sex differencesTop

Māori females were slightly more likely than Māori males to be able to converse in Māori. However, this difference varied with age. From age 45 years onwards, males were more likely than females to be able to speak conversational Māori. For those younger than 35 years, a higher proportion of females than males could hold a conversation in Māori.

Age differencesTop

Older Māori are more likely than younger Māori to be able to converse about everyday things in Māori. In the 2013 Census, 36.5 percent of Māori aged 65–74 years and 44.2 percent of Māori aged 75 years and over reported they could hold a conversation about everyday things in Māori, compared with 20.0 percent of Māori aged 15–24 years and 16.7 percent of Māori children aged under 15 years. However, the decline in people who could speak conversational Māori between 2001 and 2013 was most pronounced among the older age groups.

Table CI2.1 – Proportion of Māori speakers in the Māori population,

by age group and sex, 2001–2013

| Under 15 | 15–24 | 25–34 | 35–44 | 45–54 | 55–64 | 65–74 | 75+ | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Male | |||||||||

| 2001 | 18.9 | 22.9 | 23.6 | 25.5 | 31.7 | 45.3 | 55.3 | 55.1 | 24.6 |

| 2006 | 17.2 | 21.5 | 23.0 | 24.5 | 28.0 | 37.8 | 48.8 | 52.4 | 23.1 |

| 2013 | 15.9 | 18.7 | 20.9 | 21.3 | 23.4 | 27.5 | 38.2 | 44.3 | 20.4 |

| Female | |||||||||

| 2001 | 21.2 | 26.0 | 23.1 | 24.5 | 29.2 | 42.5 | 52.5 | 55.9 | 25.7 |

| 2006 | 18.9 | 24.5 | 23.9 | 24.1 | 27.1 | 34.3 | 46.2 | 51.8 | 24.4 |

| 2013 | 17.5 | 21.2 | 24.2 | 22.3 | 23.0 | 26.4 | 34.9 | 44.2 | 22.1 |

| Total | |||||||||

| 2001 | 20.0 | 24.5 | 23.3 | 25.0 | 30.4 | 43.8 | 53.9 | 55.6 | 25.2 |

| 2006 | 18.1 | 23.0 | 23.5 | 24.3 | 27.5 | 36.0 | 47.4 | 52.0 | 23.7 |

| 2013 | 16.7 | 20.0 | 22.7 | 21.8 | 23.2 | 26.9 | 36.5 | 44.2 | 21.3 |

Source: Statistics New Zealand, Census of Population and Dwellings

Regional differencesTop

Māori who live in areas with a higher proportion of Māori residents were most likely to be able to hold an everyday conversation in the Māori language. In 2013, the regions with the highest proportions of people with conversational Māori skills were Gisborne (30.4 percent), Bay of Plenty (28.6 percent) and Northland (26.2 percent).

Data for this section can be found at: www.socialreport.msd.govt.nz/documents/2016/ci2.xlsx